19 Nov 2021

How A Learner’s Toolkit impacts study preferences

The Churchie Research Centre has created a suite of strategies to provide high school students with the most effective study strategies drawn from proven behaviours and research in the field of cognitive psychology. The result is A Learner’s Toolkit. The toolkit is part of Churchie’s broader teaching and learning programme. The Churchie Research Centre is also sharing the research and toolkit with schools in Australia and around the world to assist all students in their learning journey. Additional information about this initiative can be found at the 2022 Open-access A Learner’s Toolkit Expression of Interest form.

The following blog post looks at how student study preferences change over time as they are exposed to more study strategies from A Learner’s Toolkit.

This is the second post in this series unpacking the impact of the A Learner’s Toolkit programme.

Study strategy preferences and use

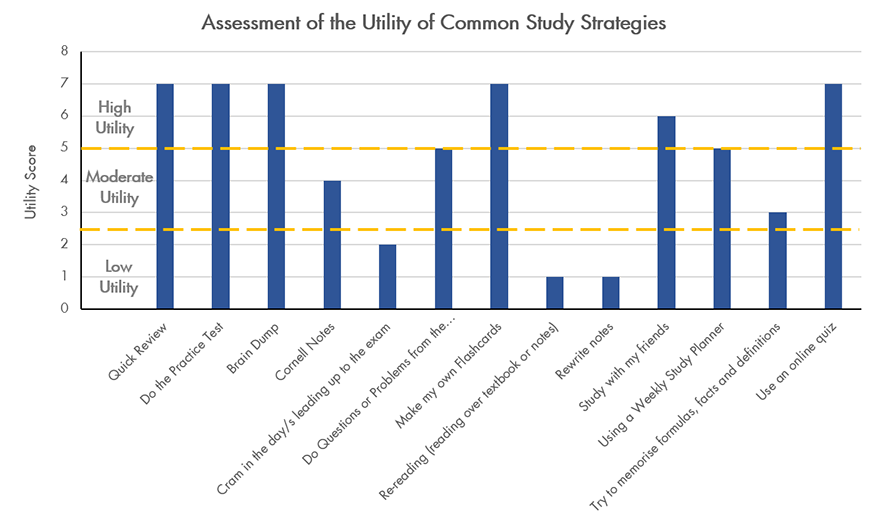

The repeated measures survey allowed students to identify the study strategies they use (Table 2). The list contained those predefined strategies initially consisting of common secondary years strategies identified earlier by Byers, Leighton, and Krzensk (2021) and Dirkx, Camp, Kester, and Kirschner (2019). Through Phases B and C, additional higher utility strategies were added. The Dunlosky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan, and Willingham (2013) study formed the basis of assessing the strategy utility (high, moderate and low). The summary of the utility assessment of common strategies used by Churchie students can be found in our recent post, Not all study strategies are equal.

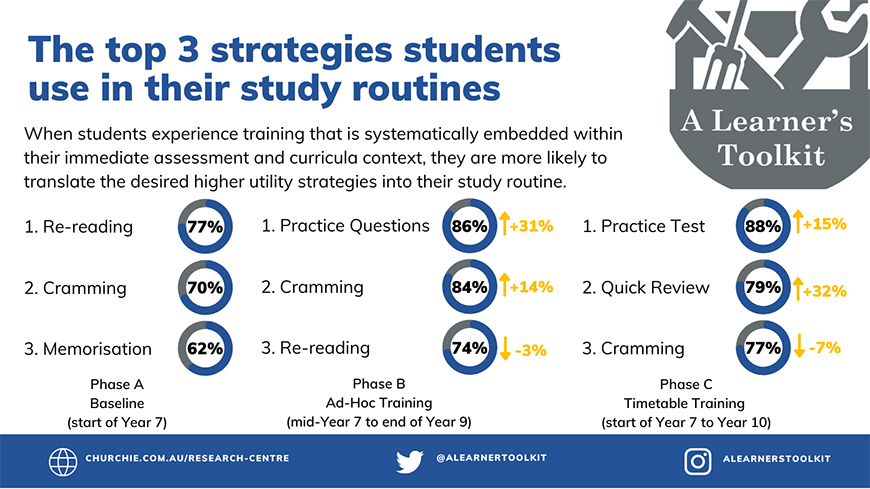

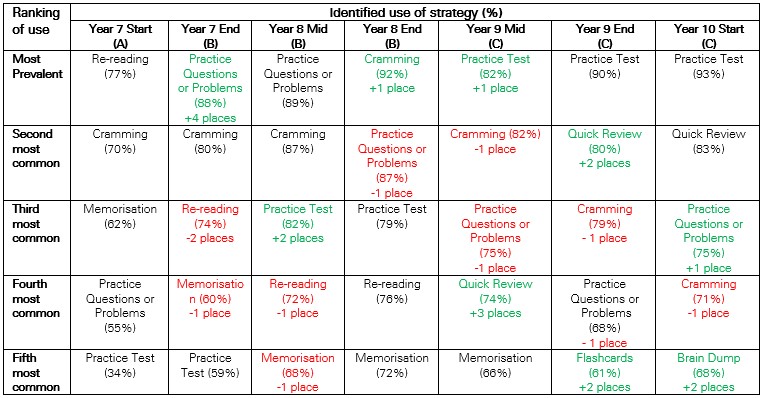

The incidence of particular study strategies did differ across the three phases (Table 1). Particular trends in specific strategies, based on their utility, were observed. In Phases A and B, the strategy preferences typically followed those found by Agarwal, D’Antonio, Roediger III, McDermott, and McDaniel (2014) and Dirkx et al. (2019). The sample favoured the accustomed practice of cramming or massed study. There was a correlation between the frequency of cramming and the application of easy-to-use, low to moderate utility strategies around the timing of assessment/examinations (Blasiman, Dunlosky, & Rawson, 2017; Karpicke, Butler, & Roediger, 2009; Kornell, 2009; McIntyre & Munson, 2008).

Table 1. Top 5 strategies used.

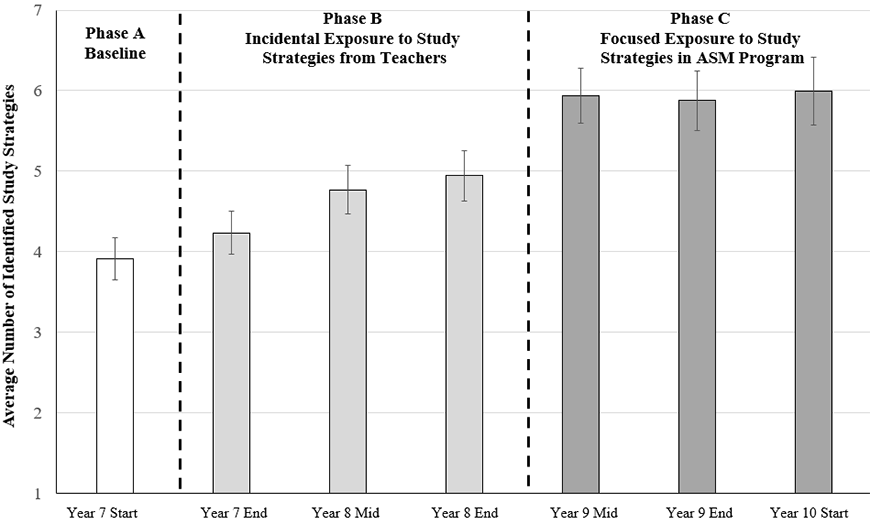

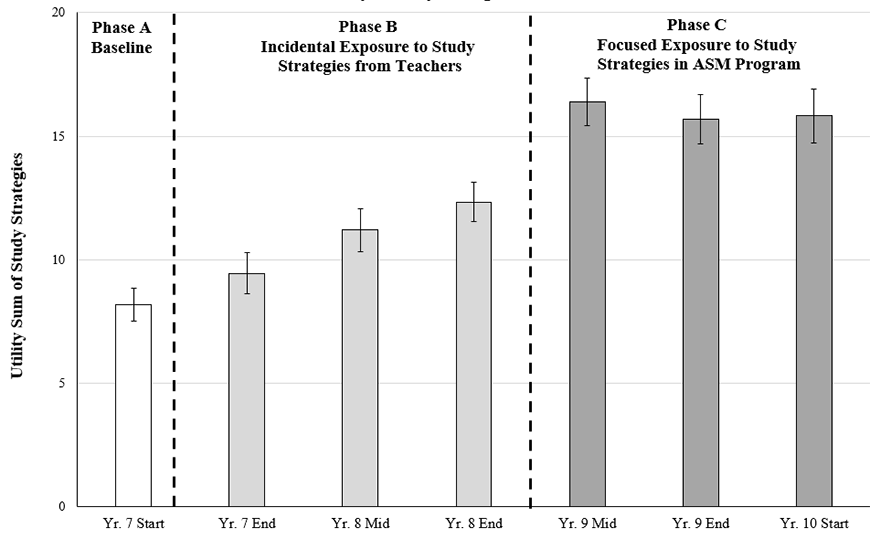

The visual analysis of the average number of strategies (Figure 2) and their utility (Figure 3) used by the sample reveals a general increase over time. The RM-ANOVA identified a significant time [F(6, 145) = 35.71, p < 0.001] and a Tau-U effect between Phase B and C of .66. At the start of their secondary schooling (Phase A), it was found that there was a high proportionate use of typically low utility strategies, namely re-reading notes and memorisation of formulas, facts and definitions, as well as the moderate utility ‘Practice of questions or problems from their textbook/OneNote’. The number of strategies and the nature of their utility is somewhat similar to those identified in the Agarwal et al. (2014) and Dirkx et al. (2019) studies. These studies found a higher innate student preference for easy-to-use, low utility review/summarising or re-reading strategies (Blasiman et al., 2017; Byers et al., 2021). The prevalence of these strategies could explain the higher student assessment of their belief around study as they derive a false sense of learning because of their easy initiation (Blasiman et al., 2017; Koriat & Bjork, 2005).

It remains unclear whether the growing practice of massed study using low or moderate utility strategies reflects poor general organisation or intentional last-minute study habits (Blasiman et al., 2017; Hartwig & Dunlosky, 2012). Alternatively, it may suit assessment in the early stages of secondary schooling, favouring recalling information from a short retention interval (Bjork et al., 2013; McIntyre & Muson, 2008). In any case, with their belief in their ability to study subsiding, the sample followed similar trends identified by Blasiman et al. (2017) and Susser and McCabe (2013). Students were observed to stick with massed low or moderate utility strategies despite the ad-hoc instruction and exposure to more efficient and higher utility strategies.

The timetable and explicit training delivered in Phase C interrogated the utility of different strategies and their applicability to their immediate subject curricula and assessment. It was not enough for students to use more study strategies. Instead, its explicit intent was to focus on those efficient and effective study strategies that affect learning through a tangible change in long-term memory. Through Phase C (see Figure 2), the sample added another strategy to their repertoire. However, compared to Phase B, the most notable change was the general increase in the overall utility of their repertoire (see Figure 3). The RM-ANOVA identified a significant time [F(6, 145) = 75.14, p < 0.001] and a Tau-U effect between Phase B and C of .97. The utility increase between Phases A and B to that observed in Phase C was underpinned by greater adoption of specific strategies, namely Brain Dumps, Cornell notes, Flashcards, Quick Review, online quizzes, and a weekly study plan. The sample maintained the prevalent use of the Practice Tests and revision involving practice questions/problems.

The rise in the use of these study strategies was also supported by translation efforts with the Humanities, Languages, Mathematics and Science faculties at the school site. The multi-faceted translation approach allowed students to apply the study strategies more often. Classroom teachers were able to shape strategies to suit the immediate assessment and relevant curriculum. The translation approach, to a lesser extent, also allowed teachers and students to identify the boundary conditions of specific strategies. Boundary conditions are the limits of a strategy and often depend on the nature of a subject, curriculum, or assessment context. Understanding the boundary conditions helps build competency that aids in using (or not using) specific study strategies.

A general decrease in lower utility approaches occurred alongside the general rise in high and moderate study strategies. The use of the low utility quartet of Cramming, Memorisation, Re-reading and Re-writing notes remained. Some students continued their use but complemented these with the addition of more moderate and high utility strategies. However, many more transitioned away from the low utility quartet and employed several moderate to high utility strategies in their place. The nature of this desired switch underpinned not just the addition of strategies but a substantive change to the utility of chosen strategies through the focus Phase C training intervention.

Reference List

Agarwal, P. K., D’Antonio, L., Roediger III, H. L., McDermott, K. B., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Classroom-based programs of retrieval practice reduce middle school and high school students’ test anxiety. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3(3), 131-139. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.07.002

Blasiman, R. N., Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2017). The what, how much, and when of study strategies: Comparing intended versus actual study behaviour. Memory, 25(6), 784-792. doi:10.1080/09658211.2016.1221974

Byers, T., Leighton, V., & Krzensk, A. (2021). Innate study behaviours and study strategies used by adolescent male students: A single school case study. Churchie Research Centre. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.28772.50564/1

Dirkx, K. J. H., Camp, G., Kester, L., & Kirschner, P. A. (2019). Do secondary school students make use of effective study strategies when they study on their own? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(5), 952-957. doi:10.1002/acp.3584

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. doi:10.1177/1529100612453266

Hartwig, M. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2012). Study strategies of college students: Are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 126–134. doi:10.3758/s13423-011-0181-y

Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17(4), 471-479. doi:10.1080/09658210802647009

Koriat, A., & Bjork, R. A. (2005). Illusions of competence in monitoring one’s knowledge during study. Journal of experimental psychology: learning, memory, and cognition, 31(2), 187.

Kornell, N. (2009). Optimising learning using flashcards: Spacing is more effective than cramming. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(9), 1297-1317. doi:10.1002/acp.1537

McIntyre, S. H., & Munson, J. M. (2008). Exploring cramming: Student behaviors, beliefs, and learning retention in the principles of marketing course. Journal of Marketing Education, 30(3), 226-243. doi:10.1177/0273475308321819

Susser, J. A., & McCabe, J. (2013). From the lab to the dorm room: Metacognitive awareness and use of spaced study. Instructional Science, 41(2), 345-363. doi:10.1007/sl 1251-012-9231-8

)

)

)

)

)